Karen Mulder (the visual arts)

Charles Strohmer Asks Art Historian and Critic Karen L. Mulder to

Take Us Inside the Visual Arts to Help Them Come Alive for Us

It is one of Christianity’s strangest ironies that though its followers serve the One who can rightly be called the Artist of creation, art itself remains an unopened, even unwanted, gift to many believers. Art, it seems, lies outside the purview of God, ignored as that which cannot broaden or enrich one’s life. Fortunately that attitude is changing, however slowly. As British philosopher and theologian John Peck has said, “Art is a kind of necessary luxury.” Many Christians are moving beyond questions about the arts’ justification to ask about how to enjoy art or how to do art in the school of the Artist. Others would like to enjoy art more, and more of it too, but they may not know the “secrets” of art appreciation.

Dorothy Sayers wrote many years ago that the church as a body has never made up its mind about the arts. It’s still true today. But hat can’t be said of Karen L. Mulder, art historian, critic, and collector, who’s had thirty years in the arts scene to make her mind up about a good many things. With visual image dominating the cultural landscape today, conveying its messages of sin or grace, I asked Karen to reveal a bit of her mind to us. She has a passion to see the arts made accessible to non-artists, so it seemed natural to ask her to initiate us, to move us around inside the visual arts in particular, that we might imagine.

Karen, a former arts editor for Christianity Today and arts director at Crossway Books, holds a Ph.D. in architectural history and currently teaches in the masters’ programs at the Corcoran College of Art and Design in Washington DC. (Originally published in Openings #12, Jul-Sept, 2001. Edited, here, for the Web, including her current bio as of 2010.)

Charles Strohmer: Why has the powerful medium of the visual arts remained closed to so many of us?

Karen Mulder: One of the issues that hasn’t been explored much by theologians and the burgeoning new group of Christian art historians is the question of distinctions, for example between high and low art (between fine art and more commercially generated art). Then there’s the distinction between what Nicholas Wolterstorff calls venerative art (art that we use to commemorate or glorify God) and art that is just made for the public. There’s also art made by professing Christians who might be speaking either to a Christian audience, as in their liturgical work, or across the border into a secular setting. If you take the distinctions into consideration, you end up having different strategies of art-making. So I’m answering the question from the art-making point of view.

CS: Would you like us to think beyond “museum art.”

KM: Yes. I want to make a distinction between museum art and art in more everyday terms because we’re free to put whatever we want to on our walls, from a very clichéd sunset decoupaged on a (usually rust-and-brown-colored) plaque with a Bible verse on it, to an original work of art from someone we might know. The former would be considered kitsch by the rest of the world, but it would mean something special to the person who owned it. In the 1970s, Christian industry discovered a huge market for it. I’m not criticizing that kind of art. I’m saying there is a distinction in the annals of art history between that and, say, something that’s a subtle still life or an expressionistic painting by someone wanting to convey more subtle truths.

CS: What’s included in the visual arts?

KM: Paintings, of course, and sculpture, but also architecture, performance art (because someone’s got to see it happening), perceptual art (where you feel things), and multi-media installation art, like Bill Viola’s, where you have to walk into a room to experience it and then things happen to you. He did one based on St. John the Divine that I think is called “The Way of the Cross.” For some people installation art can be a church-like experience in terms of depth. It’s multiple screens, usually, and has a sonic element. Sometimes there’s even an olfactory element — your sense of smell is 50% more potent than any other sense you have.

CS: Quite unlike viewing a Rubens or a Goya.

KM: Right. But in that era, that’s about the speed people could go, such as Jacques Louis David in France creating neo-classical works. He would put one painting up and it would be like a play almost; it could incite people to revolt. He made paintings of martyrs of the French revolution that were paraded on a cart through the streets of Paris so that the populace see them. That was the television, the Web, of its time. Engravings, too. Ideas were translated visually by these forms. Now, of course, you can just look “French revolution” up on the Web, or there’s countless books about. But when people were more illiterate, visual symbols were so important, and understood.

CS: What about mystery in art? We moderns are very conditioned to want everything explained. But the artist is not explaining or preaching or pounding out doctrine. She’s often conveying a mystery, sometimes a profound mystery. Not solving it, merely showing it to us. Many of us aren’t used to this level of communication. We’d like it neatly explained.

KM: Of course if the Word itself was so self-explanatory then we wouldn’t have thousands of different kinds of seminaries and denominations! The mistake that immature artists of faith often make — whether in writing, in music, in liturgical dance, or mime, or visual arts — is trying to show the whole story all of the time, the three distinct and separate moments that fuel all Western art. The first is genesis and creation, which is essentially positive and everything’s beautiful. The second is the fall, where there is breakage and separation, death and darkness. The third stage, which few artists have the capacity to illustrate in any way, is resurrection and transformation. I think even Dante in The Divine Comedy had a lot of trouble making Paradise as interesting as Inferno or even Purgatory. But my point is that Christians who are artists need to feel free to show just a fragment, a section, of life. The artist shouldn’t be under fear to express every moment.

CS: Portraying the dark side of life Christianly is quite challenging. Christians often get criticized for it.

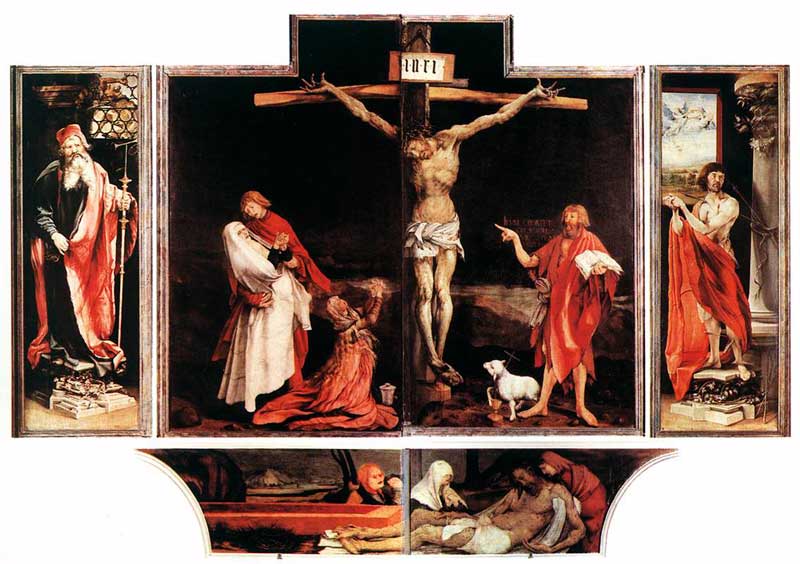

KM: Evilness is something we really sink our teeth into. That is what art has really explored in our time. If a Christian today who is an artist chooses evilness, darkness, or suffering as a subject it often gets criticized because it is assumed the artist is negating what comes after. But look at what Grünewald (early 16th century) did. Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece (a classic art history piece in Colmar, France) is the first expressionistic piece where the artist expressed Christ’s sufferings through the broken and jagged lines of the rendering. Christ just looks awful. It was painted for the chapel of a hospital where people went because they were dying from a horrible disease they got from eating bad rye bread. The patients had running sores and this Christ was painted with running sores, and of course it drives home the point of suffering.

Now the difference with Grünewald is that when you go to another side of the Altarpiece — it’s a triptych — you see the resurrected Christ in full glory: beautiful skin, glowing, incredible sense of strength and muscularity, totally resurrected with his wound marks. An artist who is a Christian will be able to portray suffering or death in a way that at least presages what the resurrection moment is, and that should allow the artist to look more deeply and realistically at suffering than someone whose art discredits suffering as maya (illusion; suffering doesn’t really exist), or who says it’s all in the mind, or that it’s gnostic. The Christian is saying we really do suffer and yet behind it is the understanding that there’s something ahead.

CS: Beautiful, then, isn’t always the point of art, is it? A work of art may show the darkness, the suffering, and not be beautiful and yet still be true.

KM: Exactly. And art is everybody’s to interpret, because it’s out there. If I see one moment in time represented by a painting, then I may have an immediate visceral reaction. I’ve said to audiences for years: now go beyond your visceral reaction and ask questions of the work. If it has integrity eventually it will answer you. You may have to talk to a curator or call the artist. That’s how I’ve learned. Most artists are pleased to get to a point of communication.

CS: What about aspects like color and line? How will some understanding of these help abstract art, for instance, open up to us?

KM: Take some young children to the abstract section of a museum and stand in front of some very large paintings, for example, by Rothko or Barnett Newman, and then ask the children, what do you see? They might say, why is it blue there? And so on. Again, you may have to talk to the curator for some answers. Or take the children to an artist’s studio and do the same thing. The artist will be happy to answer their questions and then you as an adult will learn too. For one thing, the colors are meant to work on your eyes in certain ways and the artist knows this. And with abstraction you’ve got a different set of rules, and one of those is that the artist usually works on a series not just on one piece.

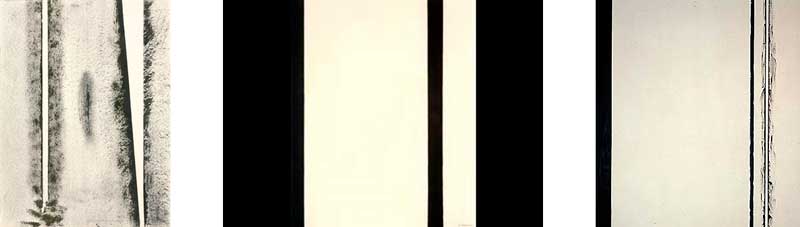

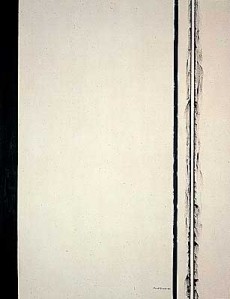

So there’s a “vocabulary” that’s set up. For example, why is the black on the bottom here and on the top there? Barnett Newman was one of these artists. He did a Stations of the Cross work completely composed of tiny little strips and boxes that were white, red, or black. Based on how these changed in his composition, he was trying to convey something. Apparently he created this series to comfort himself after his son died suddenly from a brain hemorrhage. Yet the visual vocabulary he chose to do this was highly abstract rods and squares. So the key question here is: what is the artists trying to say, rather than concluding: this is meaningless, I could have done this in second grade.

CS: I had this wonderfully surprising online experience while preparing for this conversation. I discovered a web address that lists a thousand websites (www.nhm.org/webmuseums) for museums around the world. It took me to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where I clicked on the “collections” section and was astounded. I could call up hundreds of paintings, sculptures, whatever, enlarge them, zoom in on any part of them. A great find for someone like me who lives hundreds of miles from a major museum.

KM: You made a good discovery. Another thing is this. In the twenty-five years I’ve been observing the art scene, I’d say that the question has changed from: can a Christian be an artist, to: how can I as a Christian be an artist? The first question was asking permission. Now it’s: do I have what it takes? So you have, now, more Christian departments of arts, more people getting an MFA, and so you have more potential teachers there coming out of the Christian tradition. Also, the churches are coming around to see how visually attuned the youth are. The churches have been word-attuned for so long (as our thing to hold on to), and music has helped with that.

But the visual attraction that our youth have — the quick-cut editing, the panoply of images — a lot of artists who are Christians are realizing that we have got to regain some primacy in this area of the visual. So you have a group like CIVA (Christians in the Visual Arts), which provides traveling shows that churches can rent, or sets of high quality boxed art, with text, so you know what you’re looking at. They’ve got a marvelous directory. Churches should not be fearful about using such resources. They should welcome the artists. The visual arts are a powerful medium. Christians could also consider purchasing original art done by Christians because that constitutes a relationship of trust and it would help turn around the economics.

CS: Where do the theologians fit in?

KM: There’s still a gap today between theologians — who seemed to start talking about art in the 1950s — and artists. There needs to be more theological attention to the arts. A few theologians come to mind, like Jaroslav Pelikan, whose Jesus Through the Centuries is a very helpful book. Margaret Miles, also, from Berkeley, who wrote Image As Insight. And William Dyrness, too, at Fuller. And John Peck is fantastic. He’s one of the co-founders of the Greenbelt Arts Festival. But a lot of people don’t know about John. That’s why he’s the least known theologian in the world. It’s hard to get him into the larger venues. He’s very self-effacing and doesn’t have a big school behind him.

CS: Taking time with a painting is a key, isn’t it? Like taking time with a film or a book, if we’re going to see the art start opening up to us? Often we just blow by a piece, or turn our heads, or have some sort of emotional reaction and immediately move on. How can we take time with art?

KM: There are questions people can ask. When was this done? What tradition did it come out of? Where is the artist from? In museums there’s usually wall texts or there may be handouts to read or a cassette tape you can listen to while you walk around the exhibit. Mainly, have a inquiring mind. A classic example of taking time with a work of art is a very difficult large red triptych at the Tate Gallery called “Studies at the Base of a Crucifixion.” I’ve seen so many people look at the title and then step back shocked, because it’s a Francis Bacon work where there are these terrible screaming mouths and some symbols that assault you in a kind of pornographic way. So you have to go into questions like why is he using a religious title? And there are three figures but what do they relate to? If you look into his life you find that he discovered his gay lover in the bathroom, who’d committee suicide, and that he kept incredible photographs of car crashes and horribly mutilated corpses all around his studio. So you start to add it up, he’s into death and horror, but when you search the clues further you find in his biography that he was an alcoholic and a gambler and didn’t have a lot of hope in his life except for the art he made.

Back at the three figures of his “Crucifixion” you can now say, okay, here’s an artist showing the suffering without the rest of the equation. He doesn’t know, or chooses not to know, it. I have this fond hope that in the afterlife (he died in ‘92) that he gets to have a long conversation with God about this, and that God would say, You know, you really caught the suffering. The opposite tendency for many Christians is to prettify Christ’s suffering with the white, beautifully quaffed Jesus who comes to you in Sunday school and you think: what a perfect man! But the one verse that says something about his looks says he wasn’t much of anything.

CS: How else might art open to us?

KM: Let me give you an example of a piece of sculpture that I often have people look at. It’s called Crucifix, by George Lorio. It’s about two feet high. Essentially, there’s a golden mask (gold usually refers to the divine or the holy because it’s inseparable, a totally unified color) spiked to the wall with one silver spike, which could make you think of silver pieces and Judas, and it’s spiked through a piece of fruit that’s a womb-like shape, but you don’t really know what kind of fruit it is — olive? grape? — and there’s a blood-red rip in that, which could remind you of the curtain that was ripped when Christ was crucified, and in that rip there’s a gorgeous kind of rich red, and out of one side of that fruit is a worm-like creature fleeing upwards, which is the serpent. But there’s no indication anywhere that it’s a traditional crucifix. Instead you get all these associations. Spend one minute on it and you may get the silver spike. Spend two minutes and you may get the fruit. I’ve been thinking on it for ten years. Every time I show it during a lecture and I ask “what do you see,” more and more comes out of it. Of course, you can walk away and say, I don’t see a crucifix. But then you are the one who misses out on the meaning.

Mark Rothko, Chapel installation, Houston

CS: What about the common attitude that I’m not going to view any art produced by nonChristians because there’s nothing good about it and I don’t want to get fooled by it.

KM: There’s art that I call Baalam’s Ass art. Baalam’s ass wasn’t supposed to know how to talk, but God had to talk through the ass because Baalam was so stubborn. Baalam’s Ass art involves someone who isn’t a believer and yet he can’t deny, say, the spiritual nature of human beings, of how we’re made, and as an artist he may end up framing something that is truer than what he might believe. That artist is allowing himself to be a channel for a truth that within his system he doesn’t necessarily accept. People also often react to the stereotype, that the artist is pernicious, or promiscuous, or mischievous. But for the most part, if you read their biographies, you find that the artists are really seeking truth.

CS: Still, you can get fooled by an image, can’t you? Like with some of Dali’s work. You could assume that some of it comes from a Christian worldview because of its imagery.

KM: Yes. For instance, Dali’s “Crucifixion” is a beautiful painting but it’s a bloodless Christ who doesn’t throw a shadow; a beautiful body with no signs of suffering or being tortured.

CS: A work of art may be beautiful but not “true.”

KM: Yes.

CS: Why is some art controversial?

KM: It’s really a matter of how much you know. Often when it comes to controversial pieces many people don’t know what it’s all about. They might not have even seen the piece, yet they started signing petitions against it, which just makes us look silly to the art community and we lose an opportunity for dialogue. Take Chris Ofili’s collage “The Holy Virgin Mary,” which was at the Brooklyn Museum. He is a Catholic from Nigeria, where elephant dung means different things, and his images cut out of magazines of breasts and buttocks were not about pornography but about fertility. The Saatchi brothers provoked the controversy because they were trying to sell their collection. They’re the ones who preselected these images. Chris wasn’t saying “I want to cause this big stink” at the Brooklyn Museum.

I was at the Pew Younger Scholars event at Notre Dame, where Philip Ofili, the son of the artist, was explaining this from their African-Catholic point of view. You just wouldn’t believe how different it was. But when you don’t know this, you get responses like the Christian who went into the Brooklyn Museum and started to paint over the art work with white paint! That’s the weakness of the responses we have. Rather than opening a dialogue we kill it and look like fearful buffoons rather than like people standing on the primacy of redemption with nothing to fear. There’s also a general misunderstanding about what pornography is. If people see nudity in a contemporary painting by a Christian they will tend to brand it as pornography without thinking twice and just bar it. Why, then, do we look at a Renaissance nude in the church and don’t have a problem with it because it was from the fifteenth century?

CS: Is the artist in some way like a prophet? And I don’t mean just Christians. Some artists who would not consider themselves Christian seem more prophetic at times than Christians do.

KM: It’s hard for Christians really to be salt and light. How do we do that? How do we stand out? Is it enough that our beliefs are different? I think we often fail because we merely follow whatever trend has come out, rather than coming up with original things. And yet we have access to infinite amounts of creativity because God is an infinite creator. He thought up the avocado and the ostrich. We have a Source with an endless number of creative solutions, but we don’t act like it because we operate in the safety zone. We don’t want to get anyone’s nose out of joint. Don’t want to ostracize anybody or embarrass ourselves. But just look at the prophets. They were continually going against the grain and doing outrageous acts of performance art. And those pieces were not necessarily made for an audience. They were just something God had the prophet do, like sneaking out of the city through a hole in the wall, with luggage and at night, or burying a cloth belt and digging it up weeks later. God tells someone to lay on his left side or right side for a certain number of weeks, or to marry a prostitute.

Some years ago, a man at the Christian European Artists’ Conference in Holland cut half of his hair off, on stage, and threw it up in the wind. That was his performance art. But he was taken to task for it by Christians who, evidently, didn’t know that the precursor for this was Ezekiel, who had to cut off his hair and beard and do symbolic things with the hair when the nation was under siege. It was a humiliation to lose your hair like that. So you see how things change. The word that I keep coming up with, which was inspired by Os Guinness years ago, is healthy subversion; it turns situations and people around by showing the weakness of the other position. I think of this as a form of redemption. There’s some art that can have that kind of effect on you.

CS: It’s often a problem, isn’t it, of the imagination.

KM: There’s a wonderful section in My Utmost for His Highest, by Oswald Chambers. It’s about our starved imaginations. Many people don’t know that Chambers was an artist and a poet before he came an evangelist. He died very early, so we don’t know what he would have done with that. He had a poet’s and an artist’s heart, and I think that’s why his way of words is so stunning and goes so directly to the point sometimes. And as C.S. Lewis said — who did not, by the way, have a lot of art around his house — and I’m paraphrasing, “Any work of art demands a surrender, which we’re often not willing to give.” In other words, we’d rather question it first and then maybe surrender. But Lewis says that it’s not any good asking whether it deserves surrender before you do.

(Originally published in Openings #12, Jul-Sept, 2001. Edited for the Web.)

Copyright. Permission to Reprint Required.